Art in a Pandemic

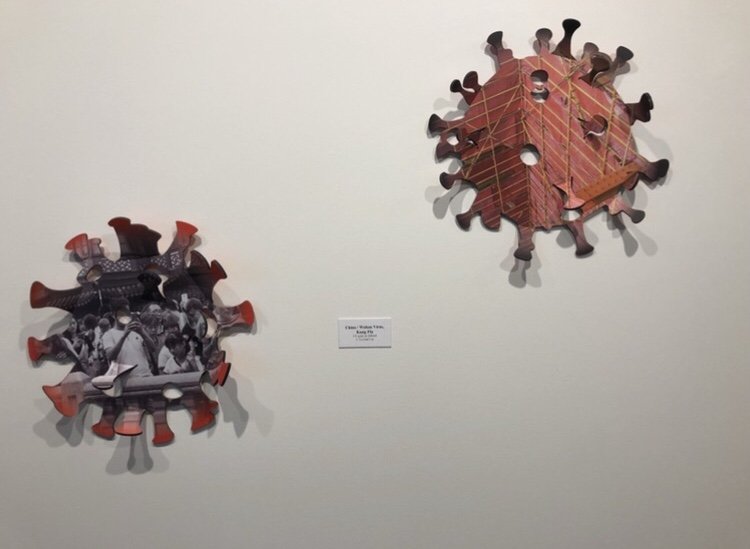

China/Wuhan Virus, Kung Flu by Joyce Yu-Jean Lee. Photo by Jamie Goodman.

For the past two years, artists across the world have been turning the COVID-19 pandemic into a form of art. Termed “pandemic art,” this type of expression is built on an artist’s reactions to the rapidly changing global landscape. Some have used their art as a form of educational material about COVID-19, while others have used it to illustrate their emotional response to the challenges brought by the pandemic.

For Joyce Yu-Jean Lee, Art and Digital Media professor at Marist College, her interpretation of the pandemic came in the form of social and political commentary on the virus’ underlying impact.

Currently part of the faculty exhibition in the Marist College Art Gallery, her piece China/ Wuhan Virus, Kung Flu showcases Lee’s creative perspective on the pandemic’s societal consequences. A diptych in the shape of the coronavirus, it tells a story about the impact the pandemic had on China. Consisting of two cohesive pieces, the diptych comments on the racial tension and social movements that were very much embroiled in the pandemic chaos.

Each piece uses photographs that Lee took during a pre-pandemic trip to China. The first piece is a snapshot of a construction site in a new arts district. The modernity of the arts district juxtaposes the traditional use of bamboo for Chinese scaffolding. The image works to showcase China’s history, culture and progress, but then becomes nothing but it’s title once the photograph takes the form of the virus.

The photograph in the next piece shows a temple that is a popular tourist site for both foreigners and locals. Lee took this shot after being taken aback by the Chinese use of cell phones. Separately, the images of a group of Chinese people and the coronavirus shape have two disparate meanings. But when put together, they make a statement. They tell a story that effectively lines up with the virus’ derogatory nicknames.

“I thought it was an interesting visual to have the faces of Chinese people be pinned to the meaning of this virus, and I think that that moniker is really an intentional one, and one that had strong impact,” Lee said.

Through the use of a photograph, Lee humanizes the people who have been affected by these harmful monikers and hate crimes. But she illustrates the reality of dehumanization in these situations by cutting out the faces or partial faces of some of the people pictured. “There are so many ways these people have been othered by us,” Lee said.

Yet, similar to the pandemic, none of this artwork was planned.

Lee’s work that is now displayed in Marist’s art gallery was originally created for an exhibition at a local Poughkeepsie gallery, Women’s Work Arts. Lee received a grant in Oct. 2020 from Arts Mid Hudson to fund this art.

Her pre-pandemic vision was to create an exhibition about transnational identity, particularly focusing on the Chinese diaspora that is present in the Hudson Valley. As a Chinese-Taiwanse-American artist, Lee was interested in exploring the social and political boundaries for transnational communities in her work.

But as the global condition regressed, Lee’s work evolved.

COVID-19 added a completely new layer to her art pieces. The work that Lee was creating prior to the pandemic started to feel irrelevant and futile to her.

Lee asked Arts Mid Hudson if she could change her show given that the pandemic greatly affected her plans for the exhibition, and they supported this. Her work developed from there.

Lee knew that she wanted her show to react to what was going on in the world – it needed to be timely and relevant. It was a stressful process to completely change the entire show, but it was also very exciting for her. “It felt necessary,” Lee said.

The artwork evolved due to the pandemic, but also because Lee wanted to capture the Black Lives Matter movement and Anti-Asian hate crimes that were all occurring at the same time. She saw overlap in both groups’ history with racism, so this all came together to inform her pieces. “Thinking about all the racial tension that happened during the pandemic, this was the layer that I think struck closest to home for me,” Lee said.

When Lee was asked to display work in Marist’s gallery, she knew she wanted to include this diptych. Because Lee was teaching remotely for the past few semesters, she decided this piece felt relevant, given that the pandemic consumed her life and greatly affected her teaching. “Faculty, because of the high esteem that I hold them in, always bring in some incredible work, and their selection process is impeccable,” said Ed Smith, Gallery Director and professor of Art at Marist.

Lee chose the shape of the coronavirus because the shape did not exist before the pandemic, yet suddenly means so much now. This figure is central to her work, and was made using an innovative technique. The pieces were created through a UV printing process, where the photograph’s ink was cured with ultraviolet light. Lee wanted to return to objecthood, so she focused on making work that was concrete. The photograph was printed onto Dibond, a material composed of two thin pieces of aluminum that cover a plastic center. Dibond enables the art to be rigid, but also bendable and curvable. So, while Dibond may be naturally flat, Lee was able to cut it in a way where it acted like a sculpture. She wanted to create something that was both 2D and 3D at the same time. Thus, giving way to what she calls a “wall relief.”

“It is so innovative how she turned a political statement into art and even took the shape of the virus as inspiration,'' said Sasha Tuddenham ‘23. “I think that just demonstrates how art, politics and science have always intersected.”

Now, Lee is revisiting her exploration of transnational identity. She has been working in Marist’s maker lab using laser cutters and creating wood etchings. Her COVID pieces have carried into her current art and have directly inspired her to do even more experimentation.